Introduction

Test-Time Reinforcement Learning (TTRL) represents a paradigm shift in how we train small to large language models. Imagine a model that improves itself on new problems without any labeled answers - learning from its own reasoning patterns during inference. This ground-breaking approach from Tsinghua University and Shanghai AI Lab challenges our assumptions about what’s required for effective reinforcement learning in large language models (LLM).

To understand TTRL’s significance, you should know about Reinforcement Learning Fine-Tuning (RLFT). If you’re unfamiliar, check out my previous blog for the basics. To read the research, click here to view the ArXiv paper.

Note: TTRL isn’t a RLFT technique, but an overlay on existing RLFT techniques like PPO, GRPO, DPO, etc.

What is TTRL?

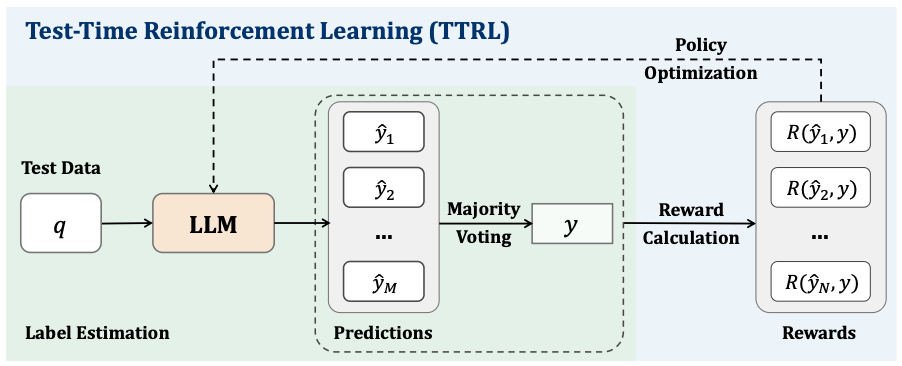

Test-Time Reinforcement Learning enables models to self-improve using only unlabeled test data. Unlike traditional RL that requires ground-truth labels for rewards, TTRL estimates rewards through majority voting on the model’s own outputs.

Think of it like a student solving practice problems without an answer key, but with prior knowledge. They work each problem multiple ways, and if most attempts converge on the same answer, they treat that as likely correct and learn from the pattern.

How Does TTRL Work?

The core mechanism is elegantly simple yet powerful:

- Generate Multiple Solutions: For each test problem, the model generates N responses (typically 64 as shown in the paper.)

- Majority Voting: The most frequent answer becomes the estimated “correct” answer.

- Reward Assignment: Responses matching the majority get

reward=1, others get 0. - Parameter Update: The model updates via Reinforcement Learning (RL) to make high-reward responses more likely.

- Iterate: As the model improves, its majority voting becomes more accurate, creating better supervision.

This creates a self-reinforcing loop where the model “lifts itself by its bootstraps.” But still how does this help the LLM get better over-time? Simple: The “bootstrapping” success happens because errors in majority voting are often uncorrelated with the model’s ability to improve. The LLM doesn’t inherently know the ground truth or possess perfect reasoning capability. Hence, it depends on prior knowledge, rewarding the highest occurring sample in a rollout and refining itself over-time using this technique.

Math behind TTRL

A consensus output or the majority-voted answer is obtained by aggregating all the answers. Then, the reward is calculated based on the similarity index (using AST or ROUGE score) between the sampled action(s) and the consensus action . The objective of the RL algorithm here is to maximize the expected reward:

This equation says that we are increasing the expectance of seeing the highest sampled output in a rollout, and increase its likelihood to appear when the same prompt or a similar prompt is seen in later succession.

The reward function in TTRL is given mathematically:

Where , is the sampled output in a rollout, and is the majority-voted output from the estimated labels.

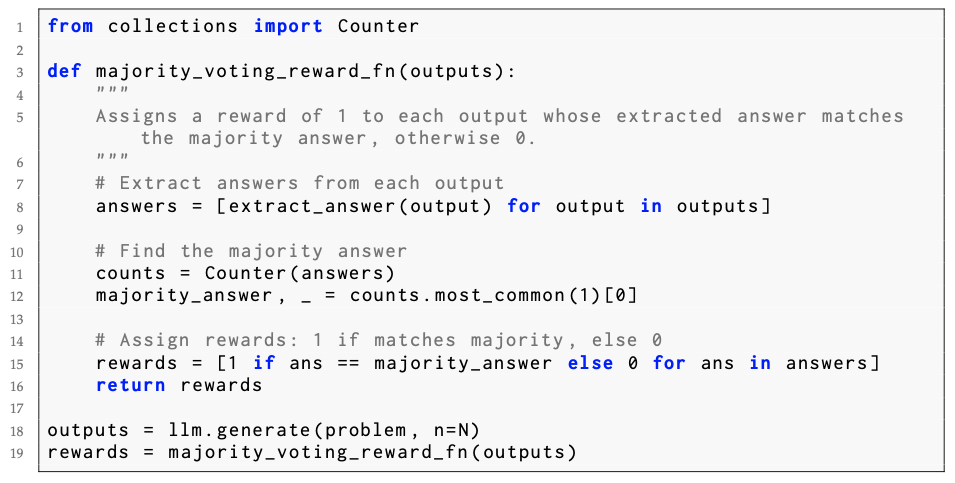

The algorithm of the majority-vote system in TTRL is as followes:

Why TTRL Succeeds: The Lucky Hit Phenomenon

The key insight is that even when majority voting produces wrong labels, the reward signals remain surprisingly accurate. Consider this example:

- (Ground truth) True answer: 3

- Model’s predictions:

[1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 4, 5, 6] - Majority vote: 2 ❌

- But predictions 1, 4, 5, 6 still correctly get

reward=0for being wrong!

This “Lucky Hit” phenomenon means reward accuracy stays high (~75%) even when label accuracy is low (~40%), providing useful training signals. If it’s still confusing, picture this - imagine an easy problem like: “Solve 12 x 13”, and the LLM model produced 8 samples in a rollout, and none of them are the right answer (Note: the model doesn’t have know the ground truth). Those were:

Now, we extract the answer from the sampled outputs in a rollout. With the majority-voting system, 146 will be the high-rewarded output. But here’s the crucial part - even when the majority is wrong, the incorrect outliers like 56, 123, 456, 5, 6 still receive the correct reward of 0, maintaining signal quality.

Results

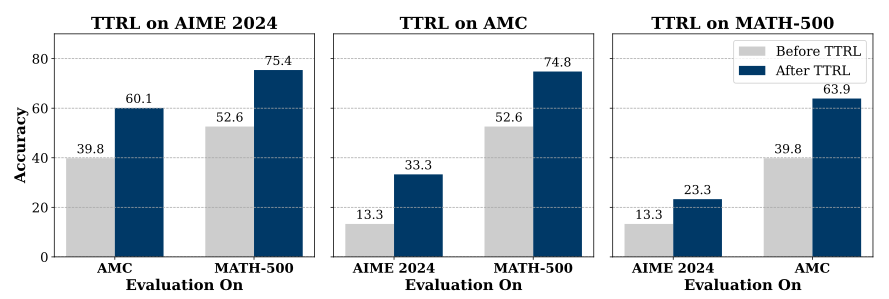

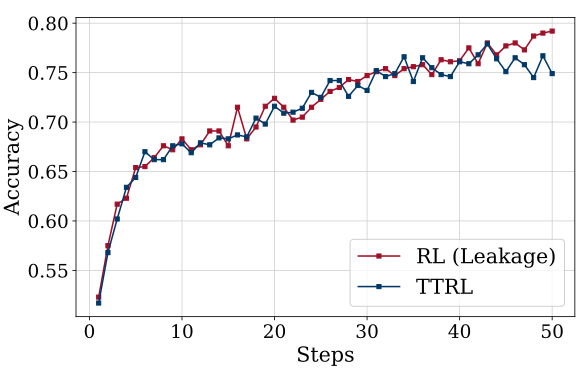

The results from TTRL are promising. For instance, take a look at the accuracy vs dataset graph shown above. Although it benchmarks on AIME2024 and MATH-500 by self-evolving using the benchmark dataset itself, this raises a critical question: Is the model actually learning to reason better, or is it simply overfitting to the specific test problems? The authors acknowledge this as “RL (leakage)” but the implications for genuine capability assessment remain concerning.

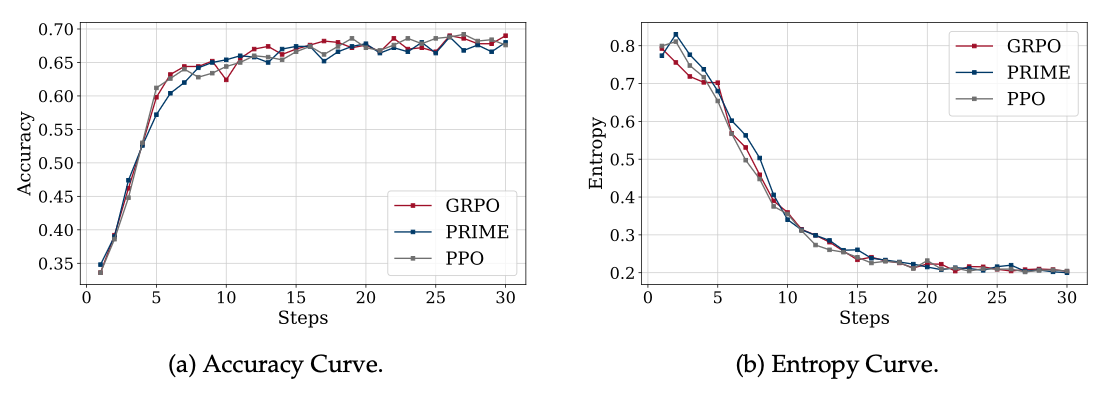

Now, check the graphs above. The accuracy increases as steps increase, which is expected. More interestingly, when the accuracy rate starts stabilizing (after step 15), the entropy has dropped and remains lower. This suggests the model refined its estimated outputs after just a few steps. Why - Because the estimated samples initially produce a mixture of diverse outputs, but as these signals evolve and refine the reward function, the best signal emerges as entropy diminishes due to signal saturation.

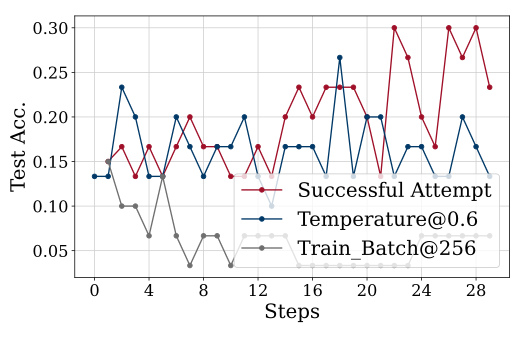

TTRL’s main weaknesses become clear in this graph (attempted on AIME 2024). The authors claim increased difficulty requires more episodic turns, but that’s only part of the story. They mention that setting temperature to 1.0 (opposed to 0.6) increases the model’s output entropy, promoting more extensive exploration. This allows better use of prior knowledge for self-improvement - crucial for challenging benchmarks. But this also highlights TTRL’s fragility to hyperparameter choices.

This graph reveals how “beneficial” leakage is to TTRL. While the authors haven’t done extensive analysis (keeping it out of scope), they mention that RL can tolerate reward estimation inaccuracies since rewards serve as directional signals for exploration. But this raises the question:

Are we measuring a genuine improvement in the LLM or is this a sophisticated memorization of a LLM?

When to Use TTRL

It excels when:

- Labeled training data is scarce or expensive.

- The model has relevant prior knowledge.

- You need adaptation to new domains at deployment.

It struggles when:

- Problems require genuinely novel reasoning as the model lacks domain knowledge.

- Hyperparameters aren’t carefully tuned.

- With increase in difficulty across dataset, the number of episodes required in exploring samples and refining the model over time takes a long-time.

Applications

- Competition mathematics: Adapting to new problem styles.

- Code generation: Learning from test cases without solutions.

- Scientific discovery: Exploring problems where ground truth is unknown but with prior knowledge in the domain of interest.

- Specialized domains: Where human labeling is expensive or requires expertise.

Reflection

TTRL is definitely a compelling venture into online-RL and self-evolving language models, tapping into continual learning. Its impressive results - from small models (Qwen-2.5-1B) to large ones (Qwen2.5-32B) - show exponential accuracy improvements through self-refinement. However, the major pitfall I see is this: although it claims to work on unlabeled datasets, it still requires prior knowledge in that domain to estimate useful labels for self-refinement. Without this foundation, returns from the signals appear minimal at best.

Furthermore, using test datasets for both training and evaluation undermines the paper’s claims. While the research is properly conducted, this circular evaluation seems problematic. Dynamic benchmarks with adversarial dataset creation could better assess TTRL’s true capabilities.

Yet TTRL demonstrates something profound - models contain far more latent capability than they initially express. A 1.5B model improving from 32.7% to 73% on MATH-500 suggests our models “know” more than we realize; they just need better ways to access that knowledge. This raises fundamental questions:

If models can be their own teachers, what does this mean for continual learning? Could future models self-improve throughout deployment, adapting to each user’s needs?

Acknowledgment

All content is for educational purposes. Credits to the authors from Tsinghua University and Shanghai AI Lab for developing TTRL. Read the full paper for technical details.